Alas, when the Ice is Crying

The glaciers are melting in Greenland. And Man is worried about the future of the world. In search of clues in a natural paradise.

By: Christoph Quarch | Photos: Sven Nieder | Translation: Donna Weidner

Is the glacier laughing or crying? Nukartaa does not need to search for the answer. “She is crying,” he says. “The ice is crying and the river that you are looking at there, is carrying her tears to the sea.” Nukartaa says this with a look of concern. Even he, a Greenlandic Elder, is close to tears. I am reminded of what I saw yesterday: turquoise blue lakes far inland lying on top of the ice. They looked like eyes peering up from the depths at the sky. We were on approach, landing in Kangerlussuaq. Then, my heart jumped for joy. But now, I am uneasy: The glacier is crying. Kangerlussuaq is Greenland’s door to the world and the hub for Greenland’s domestic flights. It takes an Airbus A380 four and a half hours to fly you there from Copenhagen. Even if you want to come to Greenland from nearby Canada, you must choose this route. Any traveler with Greenland as a destination cannot bypass the capitol of its former colonial ruler. Only from Copenhagen are there flights to the largest island in the world. And they are very expensive.

Kangerlussuaq is Greenland’s door to the world and the hub for Greenland’s domestic flights. It takes an Airbus A380 four and a half hours to fly you there from Copenhagen. Even if you want to come to Greenland from nearby Canada, you must choose this route. Any traveler with Greenland as a destination cannot bypass the capitol of its former colonial ruler. Only from Copenhagen are there flights to the largest island in the world. And they are very expensive.

Nevertheless, I am here sitting in the take-away pizza place across the street from the airport. It is a former US Air Base that was built during the Second World War, a place for bombers to land and refuel on their way to Europe. Later, it was also used by the “Candy Bombers” on their way to Berlin. Nowadays American transporters climb into the pale blue summer sky even though the field has long since been handed over to civilian aviation. There’s not much more really here; one hundred houses at most are grouped about the airstrip. Or better said, container type housing, with its’ demur charm of a former Air Base, including the pizza place. That’s where I met up with Nukartaa. We both have the same destination: an event out in the wilderness that will begin in a few days time. In a camp at the foot of the Big Ice—a massive river of ice that stretches 12 kilometers from the inland ice winding down onto the gentle, green hillsides of west Greenland. We were invited by Nukartaa’s brother. His name is Angaangaq; an Inuit like him, and exceptional to boot.

Angaangaq had been chosen to represent his people at the United Nations. He is a respected Elder among his people. He travels the world recounting the drama that is taking place in his home: “The Big Ice is melting.” And it is time to face up to it. This is why Angaangaq extended an invitation to the far reaches of the world. He wanted to talk about the spiritual meaning of climate change with people from the western world, with representatives from indigenous peoples, with the Elders of his own people. And so I too set out in July 2009 to get to know Greenland: the country where climate change is not some future scenario but a daily reality, the country where the glaciers are crying.

Are they really? I want to know. With Adam, an affable Inuit, I drive to the Big Ice in a huge adventure-seeking vehicle, the likes of which you could bomb across the moon in. It takes us just about an hour to drive the 25 kilometers that separate Kangerlussuaq from the ice cap. Endless ice stretches the remaining 800 kilometers to the east coast? Endless? When I peer into the grey-brown floes of the Kangerlussuup Kuua I’m not so sure. Gigantic masses of water from the glacier drive the current that ends in Kangerlussuaq, water that was buried almost 200 kilometers inland from the west coast.

The tract to the glacier follows the Watson River along an area where one would tend to think that climate change had already unmercifully struck. There are sand dunes. The thermometer registers 28 degrees Celsius. You would think we were in the Sahara had not been for the glistening white band on the eastern horizon—had it not been for the ice. Yet still, the impression is not altogether wrong. We crossed over an arctic desert—hardly any precipitation falls here on the tundra. And in summer, the sun shines 20 hours a day on the land. Thereby, the glacier sweats in any case.

Shortly thereafter I am standing before a wall of ice. The sight is breathtakingly beautiful. The Watson River has bored caves into the glacial tongues. They shimmer turquoise-blue. It must be fifty to one hundred meters high. Ice, wherever the eye can see. I calm myself: it will take years for this to melt. Maybe the ice is eternal. In that moment a primeval thunder booms from the glacier. A gigantic tower of ice breaks off falling into the river creating a meter high fountain. “She’s screaming,” says Adam.

It became clear to me it was still not that easy. In any case, the Greenlanders were worried about their ice. And maybe the world should take their lead. Adam spoke: “The ice is melting quickly. It has become porous.” Normally during this time of year, the Polar Lodge—the tourist organization Adam works for, offers excursions on the ice. This year they had to call them off. The ice screws that attach the tents to the ice, no longer hold. Then he points to the moraines alongside; like textbooks they flank the stream of ice. Then even I notice they are much higher than the ice. It just so happens that the ice has lost 50 to 100 meters of its thickness. “In the last ten years alone,” says Adam. And he suggests I take the tour to the Ice Cap with his colleague Christian the next day to see the situation more closely; especially since that would make it easier to get to Angaangaq’s campsite.

This time I travel up the gravel road in a bus that was remodeled from a truck. The road, (a downright euphemism), was built in 1994 by Volkswagen when they had this glorious idea to photograph their newest vehicle far inland on Greenland’s ice. For this purpose, a 40-kilometer tract—Greenland’s longest road—was carved into this breathtakingly beautiful landscape. It meanders along the massive ice of the Russell Glacier, past crystal clear lakes and thundering waterfalls. Even the cuddly musk oxen that graze freely here show themselves along the roadside. If you had to actually walk this route, it is a tour one should not pass up, especially not the end of it. Suddenly the bus is standing before a gigantic heap of rubble—the moraine, accumulated glacial debris, from the inland ice. “When VW built this road, they were able to drive directly onto the ice,” said Christian. Today, you need to climb up 40 meters of moraine in order to step onto the frozen sea. And it isn’t even as frozen as it appears to be from high atop the rocks. Millions of small streams wind across the brittle ice. There is no doubt that it is melting quickly, even though the endless white horizon appears to promise that the ice is endless.

This time I travel up the gravel road in a bus that was remodeled from a truck. The road, (a downright euphemism), was built in 1994 by Volkswagen when they had this glorious idea to photograph their newest vehicle far inland on Greenland’s ice. For this purpose, a 40-kilometer tract—Greenland’s longest road—was carved into this breathtakingly beautiful landscape. It meanders along the massive ice of the Russell Glacier, past crystal clear lakes and thundering waterfalls. Even the cuddly musk oxen that graze freely here show themselves along the roadside. If you had to actually walk this route, it is a tour one should not pass up, especially not the end of it. Suddenly the bus is standing before a gigantic heap of rubble—the moraine, accumulated glacial debris, from the inland ice. “When VW built this road, they were able to drive directly onto the ice,” said Christian. Today, you need to climb up 40 meters of moraine in order to step onto the frozen sea. And it isn’t even as frozen as it appears to be from high atop the rocks. Millions of small streams wind across the brittle ice. There is no doubt that it is melting quickly, even though the endless white horizon appears to promise that the ice is endless.

In the evening, I meet up with Angaangaq, the Shaman and Elder of his people. His welcome speech for his guests is dramatic: “Way up north, in January of 1963, hunters came to the Elders of their clan and reported that they had seen a trickle of water dripping from the ice. It was minus 35 degrees.  The Elders thought the men had been ‘knocking a few back’ at the US Air Base in Thule. Three months later, seeing it with their own eyes convinced them they had not been drunk. And by then, the trickle had become a stream.” Angaangaq, emphatically continues, “Every day, the ice melts 20 centimeters and at the same time the trees are standing up. They used to crawl along the ground. Today they are as tall as a man.” And then a moment of intense emotion overtakes the man, “The reason for this is your ways of living. You have lost your center and we have to bear the brunt of it!” The glacier grumbles nearby and sends an icy breeze down the valley. I’m freezing. Angaangaq continues, “Whole countries will disappear when Greenland’s ice has melted into the sea! Why?”—He gazes around the circle: “Because you are torturing Mother Earth, because you are raping her, because you are ignoring the knowledge of the indigenous people. We were the first to set foot on the Big Ice—and we will be the last!” he said. “But no one listens to us. You send your scientists when you should be listening to the words of our Elders. They have been living for thousands of years with the ice. No one knows it as well as they do.”

The Elders thought the men had been ‘knocking a few back’ at the US Air Base in Thule. Three months later, seeing it with their own eyes convinced them they had not been drunk. And by then, the trickle had become a stream.” Angaangaq, emphatically continues, “Every day, the ice melts 20 centimeters and at the same time the trees are standing up. They used to crawl along the ground. Today they are as tall as a man.” And then a moment of intense emotion overtakes the man, “The reason for this is your ways of living. You have lost your center and we have to bear the brunt of it!” The glacier grumbles nearby and sends an icy breeze down the valley. I’m freezing. Angaangaq continues, “Whole countries will disappear when Greenland’s ice has melted into the sea! Why?”—He gazes around the circle: “Because you are torturing Mother Earth, because you are raping her, because you are ignoring the knowledge of the indigenous people. We were the first to set foot on the Big Ice—and we will be the last!” he said. “But no one listens to us. You send your scientists when you should be listening to the words of our Elders. They have been living for thousands of years with the ice. No one knows it as well as they do.”

The group of 150 people applauds. They then fall silent as the 81-year-old Hansiina seizes the moment, “Our forefathers went about carefully with the earth. They took from her no more than they needed. They respected the law of balance. They were not rich with things, but they were rich in heart,” she said, “But then others came and put us down. They believed they knew better than we—and they destroyed the land. Now the time has come for us to share our wisdom with the world so that the earth may heal!” Her admonishing words will not be the only ones during this thought-provoking gathering. A unanimous choir of wise indigenous participants rises up. Whether from New Zealand, Nepal, Siberia, Zimbabwe, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada or the USA, they all said the same: The world is changing, its balance is disturbed. It is up to us to restore that balance. If we do not do it, then nature will—even if many countries need to go under in the process. Jane Goodall even agreed. The UN Ambassador of Peace came up north to show her solidarity with the Elders.  “How can it be that man—the most intelligent being—is destroying the earth?” she asks. And she answers her own question, “It appears as if we have been abandoned by our good spirits. It appears that we have lost the connection of our intellect to our heart.” She plays on the words of her host. Angaangaq ends his fiery speech with an appeal: Only when man melts the ice in his heart will he really be able to deal with the outcome of the melting ice. Climate change can no longer be stopped. Some of the assembled Shamans and Elders see it in another way. Dave Courchene, a native north American, believes the melting ice will ring in a new era in human history because the melt water will free the spirits—the good ones, that we wrongly believe, have deserted us. And the Shaman Eduardo from Bolivia believes Mother Earth will take care of her own balance. We only need to trust her. Hm, I think to myself, and note it down as indigenous conceivability. But, when I hear whispers of esoteric interpretations from some European shamanic students in the camp about 2012 and the Mayan calendar, I have a heretical thought. Maybe Mother Earth has simply had it with us! Maybe she’s just thinking: Thaw the shit away! But perhaps Haru Kontanawa is right—complete with feathered headdress, the young Native Chief from the shallows of the Amazon River Basin says: “At home, the forest is being destroyed. Here, grows a new one. I see a blooming Greenland.” So much optimism is even a bit too much for the native Greenlanders. I talk with Laali, a pretty 35 year-old Inuit woman who works in Nuuk in an Internet Café. Laali is worried about the polar bears in the northern part of the island. They have been attacking and eating one another because, due to the melting ice floes, they can no longer hunt seal. But, she has noticed the awareness amongst young Greenlanders as to how precious the natural paradise in which they live is. And that it will depend on all its financial development to maintain it. Oil would be good, she says, if we deal with it wisely, similar to the Norwegians.

“How can it be that man—the most intelligent being—is destroying the earth?” she asks. And she answers her own question, “It appears as if we have been abandoned by our good spirits. It appears that we have lost the connection of our intellect to our heart.” She plays on the words of her host. Angaangaq ends his fiery speech with an appeal: Only when man melts the ice in his heart will he really be able to deal with the outcome of the melting ice. Climate change can no longer be stopped. Some of the assembled Shamans and Elders see it in another way. Dave Courchene, a native north American, believes the melting ice will ring in a new era in human history because the melt water will free the spirits—the good ones, that we wrongly believe, have deserted us. And the Shaman Eduardo from Bolivia believes Mother Earth will take care of her own balance. We only need to trust her. Hm, I think to myself, and note it down as indigenous conceivability. But, when I hear whispers of esoteric interpretations from some European shamanic students in the camp about 2012 and the Mayan calendar, I have a heretical thought. Maybe Mother Earth has simply had it with us! Maybe she’s just thinking: Thaw the shit away! But perhaps Haru Kontanawa is right—complete with feathered headdress, the young Native Chief from the shallows of the Amazon River Basin says: “At home, the forest is being destroyed. Here, grows a new one. I see a blooming Greenland.” So much optimism is even a bit too much for the native Greenlanders. I talk with Laali, a pretty 35 year-old Inuit woman who works in Nuuk in an Internet Café. Laali is worried about the polar bears in the northern part of the island. They have been attacking and eating one another because, due to the melting ice floes, they can no longer hunt seal. But, she has noticed the awareness amongst young Greenlanders as to how precious the natural paradise in which they live is. And that it will depend on all its financial development to maintain it. Oil would be good, she says, if we deal with it wisely, similar to the Norwegians.

The message from the Elders has not bypassed her: “We must deal with the land cautiously,” she says, “and bring together the wisdom of the old ones with the knowledge of the young.” Maybe that’s really the recipe. Maybe what the Elders say is right: “We must find the center and hold the balance. And, by the way, melt the ice in our hearts.” Greenland is a good place for this. Not only because of its arctic summers that don’t allow you to tire. Not only because of the sun that warms your heart for 20 hours at a time, but mostly because of the fragile beauty of this quiet island. Even if I had a heart of stone, the sight of the Greenlandic ice in the warm light of the midnight sun is heart softening. On the flight home I can’t keep my eyes away from the window. The icy world below me sleeps in a delicate rose-colored light. On Air Greenland’s pop channel Michael Jackson’s Earth Song is playing: “What have we done to the World?” I ask myself the same question.

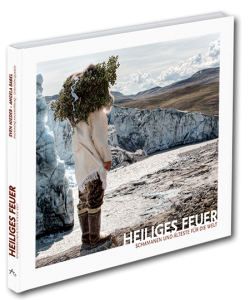

The book Sacred Fire Ceremony (German):

Heiliges Feuer – Schamanen und Älteste für die Welt

Heiliges Feuer – Schamanen und Älteste für die Welt

Grußwort: Angaangaq Angakkorsuaq

Fotografie: Sven Nieder

Text: Angela Babel, Dr. Christoph Quarch

Gestaltung: Björn Pollmeyer

156 Seiten

Format 25 x 29 cm

Aurum, 2010

FSC, CO2 neutral (Forest Carbon Group)

ISBN 978-3899013566